It was the strangest kidnapping case Western New York had ever seen, and it all tied back to a Super Bowl squares pool, an unexpected game and the one man who got in over his head

The muffled screams escaped through the narrowly cracked window and into the frigid winter afternoon air. That’s what drew attention to the blue pickup truck, otherwise inconspicuous in the grocery store’s side lot.

Wrights Corners is a hamlet within the towns of Lockport and Newfane, some 35 miles north of Buffalo, and Tops Friendly Market is in the bustling part of town. It sits just off a two-lane highway, a little past a quiet stretch of modest ranches and colonials; unspoiled land where a property line has room to breathe, some playing host to a pop-up camper or ride-on lawnmower. A man could wash his car, get insured, buy a case of beer and order a Big Mac Value Meal all within a few hundred yards.

This is where James Moscato, a decorated police officer seven years out of the academy, found himself, responding to a dispatch about a distressed man in the back seat of a parked vehicle. Moving closer, he saw the guy’s neck was tied to the metal bars that support the driver’s seat headrest with a length of rope. His hands and feet were bound together with duct tape.

A thick snow flurry moved through, piling on the windshield as Moscato pulled out his knife to slice the tape and bag it for DNA evidence. Ever-so-slight ligature marks peeked out from behind his black hooded sweatshirt. He was older, in his 60s. Sandy hair, hazel eyes, goatee. He told Moscato how he’d been kidnapped two days earlier by a pair of men, robbed of the $16,000 in cash he was carrying and forced to drive around the area—everywhere from Rochester to Lewiston—while the captors plotted their next move. He told them of the first night, when he slept in a hallway of a stash house with a cap pulled over his eyes but couldn’t risk running even when he was sure his captors had fallen asleep; he was certain he’d be shot. The second night, he said, they’d discarded him here along with his truck, just off where New York routes 78 and 104 merge, a good 30 minutes north of his North Tonawanda home.

He might have recognized one of the two—he was from work, Tim. Maybe. But he wasn’t sure and didn’t have a last name. The other guy? No clue. But he figured they were ducking security cameras based on their erratic movements when they arrived at Tops.

As he told his story the man shook, maybe because he was scared, or cold, or both. Moscato handed him a protein bar and a water, letting him sit in the back of the cruiser to calm down. After about 20 minutes, there were multiple police SUVs on the scene, with a second officer combing through the pickup to bag evidence and a third speaking with the Tops employee who first heard the man’s cry for help and phoned the local dispatcher. This time of year, after weeks of slush and ice, it seems most police work is devoted to cars sliding off the road. A kidnapping case would involve resources from all over the county: a forensic team, a fingerprint tech, a video unit to document the scene. They’d probably have to borrow investigators from two towns up the road, a 25-minute drive in bad weather, but it might be a necessity. Moscato’s adrenaline spiked. Now 35, he was in his late 20s when he left a desk job to join the force. This is why: days like today, cases like this.

As the man’s account of the abduction weaved its way into a full picture of how and why he ended up here, it only got stranger. He’d been running a big-money Super Bowl pool at work, and he still owed a few people money. Lots of money. That’s where all this trouble started, he said, why things got out of hand.

And so began one of the most bizarre kidnapping cases Western New York has ever seen, right there amid the afternoon coupon crowd buying shampoo and lunch meat; a collision course between sharp cops, sloppy criminals and the Super Bowl no one expected. In less than two hours, an arrest was made.

* * *

The Unifrax plant sits just off I-190, before the highway crosses

the Niagara River onto Grand Island, situated at the approximate midpoint between Buffalo and Niagara Falls. Lit up at night in the fast-closing dusk, it looks like a Costco made almost entirely of metal roofing with an American flag waving out front. Driving around the area, one might feel as if they’re circling the edge of our universe—black sky above bleeding into black water somewhere in the near distance below, the burning nasal sensation of endless cold barreling in, few signs of life between the refuge of car and workplace heat. Inside, they make specialty fiber products; perhaps your car’s fiberglass insulation was manufactured here.

This is where Robert Brandel was employed for the better part of a decade. Those who know him describe a wiry, “grandfather” type with a surprising amount of energy for someone his age. Bobby was the kind of guy who would bring candy bars into work to break up the monotony of a long shift. Or if he saw a group he knew out at the bar, he’d make sure to pick up the tab. He’d talk about a big family, a bum knee and his blackbelt. He was always available to take shifts for other people.

“One of the nicest guys we worked with,” said one Unifrax worker. “And one of the best workers too.”

Brandel began a version of the Super Bowl squares pool seven years prior, and his affable disposition seemed to make him the ideal friendly neighborhood bookie. In February 2018, only days after the Eagles beat the Patriots in

one of the biggest upsets in Super Bowl history, Brandel began simultaneously paying winners of his seventh pool and collecting for next year—he would always start the collection process immediately after the previous year’s Super Bowl payouts. He offered payment plans and jotted all his clients down in a little notebook.The $500-per-square buy-in price attracted the kind of relative high rollers who craved a meaningful piece of action. This was potential vacation money. New-truck money. Maybe even fresh-start-someplace-warmer money.

“Word spreads when you have a pool for $500,” said one participant.

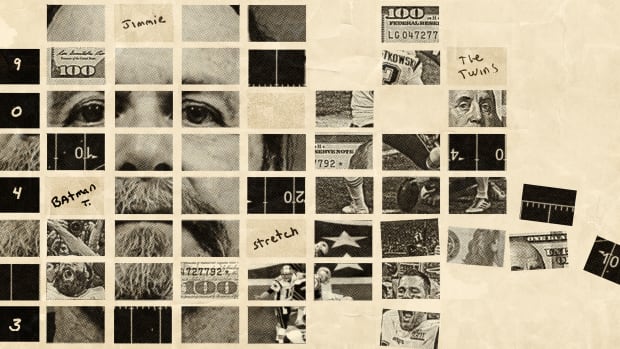

Brandel told coworkers he took the game over from a bar he frequented, which would explain why more than a few names were unfamiliar to the people from work who bought squares. The finished product was a scribbled tapestry of two worlds coming together, the full Christian names one might use in an office, alongside eloquent sobriquets you might use at the bar. Like “Stretch” or “The Twins.” Or “Boner.”

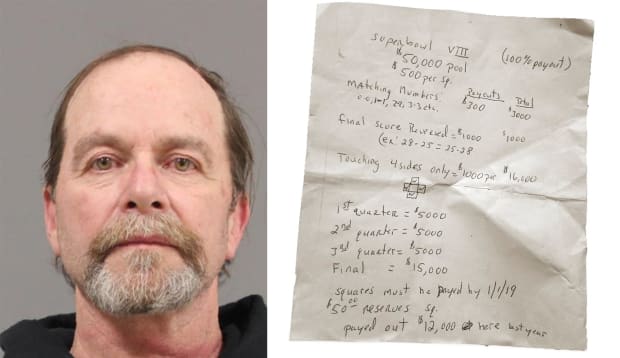

His payout structure and schedule for dues were listed in a handwritten flier given out around the plant, laying out the $50,000 in prizes and that Unifrax employees had cashed in for a combined total of $12,000 the previous year.

It was hard for anyone throwing their money down to imagine that, in less than a year, thousands of dollars would be unaccounted for. Or a Xeroxed copy of the squares would be in a police evidence locker. Or that, if you spend a few moments disassembling and reshaping the bits of anecdotal knowledge one might collect and store on coworkers, it becomes clear how little you really understand the people who pass through your life every day.

* * *

Super Bowl squares are set up similar to that of a Battleship board or a cow flop grid.

A pool consists of 10 vertical columns and 10 horizontal rows thatched together and numbered from zero to nine. One Super Bowl team gets the columns and the other gets the rows, and each of the 100 squares inside are purchased individually. At the end of every quarter, the person whose square corresponds with the intersection of the second digit of each team’s score wins a prize (for example, a 14–7 score at the end of the first quarter pays out the owner of the square at row 4, column 7). The final score usually pays out the highest sum.

The numbers assigned to each row and column are selected at random once every box of the pool has been sold—in other words, you don’t get to choose your numbers; it’s luck of the draw. Anthony Zonfrelli, an investment analyst, while a member of Harvard’s prestigious Sports Analysis Collective, studied 30 years of playoff and Super Bowl scoring data to map the most successful payout squares back in 2013. He called the project one of the easiest given how top-heavy football scoring is—mostly sevens, zeroes and threes. A heat map he and two other partners produced showed that landing certain combinations, like 7–0, 0–0, 7–7, 0–7, 3–7, 7–3, 4–0 and 3–0 yield an exponentially higher rate of payout than most others. Conversely, squares like 9–1, 9–2, 2–2, 2–5 and 5–6 had never been hit over the three decades of analysis that they’d done.

In Brandel’s pool, bonus money was awarded before the game even began, to the 10 participants who had “matching numbers” (0–0, 1–1, 2–2, etc.). There were also bonuses for the squares to the top, bottom, left and right of the winning squares in each quarter, and to the square that had the reverse of the final score (for instance, if row 4, column 7 was the final score, row 7, column 4 would receive the “reverse” prize).

By the end of championship Sunday last January, when the Rams pulled off a (controversial) overtime upset in New Orleans and the Patriots did the same in Kansas City, many expected Super Bowl LIII to be a high-scoring laser show. The Rams entered as the league’s second-ranked offense, while the Patriots came in at No. 5. The Rams had scored 30 or more points in 13 of the 18 games they had played leading up to the Super Bowl, while New England had done the same nine times. The Patriots also featured the greatest quarterback in league history, a man who had made regular appearances in games like this seem almost banal. The year prior, the Eagles and the Patriots lit up the scoreboard in a 41–33 shootout.

Vegas bookmakers set the initial projected scoring total (for over/under bets) at 59, the highest in Super Bowl history, fitting for the culmination of a season that featured the zenith of an offensive revolution that had been sweeping the sport over the last calendar year. The game instead was more a signal of the dust settling. One oddsmaker at a major casino said that most of the tenured betters they saw in the gambling world began piling on the “under”—by kickoff, the total had been dropped to 55.5, 56, or 56.5 at most sports books. There was a collective feeling that too many things would have to continue going right for the game to live up to its high-octane billing.

And so it went. With two weeks to prepare, coach Bill Belichick and de facto defensive coordinator Brian Flores unveiled a brilliant defensive game plan, spooking young Rams quarterback Jared Goff with a mix of simulated pressures and fake blitzes and—for the Patriots—unique zone-coverage looks. New England followed a “blueprint” on the Rams by putting six defenders on the line of scrimmage to smother Todd Gurley and L.A.’s vaunted outside-zone rushing attack. They used linebackers to demolish many of Los Angeles’s quicker motion players at the line of scrimmage, which disrupted the rhythm of their plays. The Rams, meanwhile, countered with a defense that would morph almost instantly from man to zone coverage, a gimmick that successfully forced Tom Brady to throw into windows of space that appeared open but would soon slam shut—New England’s opening possession ended with Brady, fooled by a coverage, throwing only his sixth Super Bowl interception in nine games.

A scoreless first quarter (squares winner: 0–0) was remembered best for Patriots kicker Stephen Gostkowski pulling a 46-yard field goal attempt wide left. He made up for it with an early-second-quarter kick, which stood up as the only points of the first half (squares winner: 3–0). The Rams had a chance to take the lead midway through the third quarter, when a busted coverage allowed receiver Brandin Cooks to streak behind the secondary unguarded, but Goff spotted him too late and put too much air under the ball, allowing veteran cornerback Jason McCourty to deflect the pass at the last moment. Three plays later, the Rams settled for a game-tying field goal with 2:11 left in the third, the quarter’s only points (squares winner: 3–3). Finally in the fourth quarter, Brady connected with Rob Gronkowski on a couple of long passes, setting up Sony Michel’s two-yard touchdown plunge. After Stephon Gilmore intercepted Goff on the ensuing drive, they turned to the ground game to ice it, running it on eight consecutive plays, covering 72 yards, to set up another Gostkowski field goal to stretch the lead to 13–3 with 72 seconds left.

The Rams had one last gasp, moving the ball to New England’s 30 with 10 seconds left. They sent out the field goal unit: The plan was to kick a field goal, recover an onside kick, and have time for a final Hail Mary pass, a desperation scenario for the Rams but an ideal one for any pool participant with the 3–6 square. Ideal until Greg Zuerlein pulled the kick wide left. Brady came out in victory formation for the Patriots—and for the 3–3 square in office pools everywhere, whose nights had just transformed from fortuitous to unbelievable.

That was especially true in Brandel’s pool, where 3–3 paid out for the final and third-quarter score, as well as for “reverse” of the final, and the pregame prize for a “matching” square. When the game clock hit zeroes, someone at Unifrax was in line for $22,000.

* * *

Brandel pulled around the corner and saw the truck idling outside his house, three grown men piled inside. He knew who it was and why they were there. This was the culmination of an extended period of silence in the form of avoided phone calls and unreturned messages, and confusion sewn by sporadic and increasingly bizarre explanations. It was three weeks after the Super Bowl, and owners of the winning squares were still waiting to collect.

Plans made for cash drop-offs were often canceled, at first for pedestrian reasons (Sorry, had to go out of town!). Soon the excuses became more specific but outlandish (Sorry, extended vacation to watch a PGA tour Pro AM, couldn’t pass up a chance to see Romo!). That gave way to the almost unfathomable (Sorry, was on my way but got pulled over by the cops, hope they don’t find the cash!).

There had been jokes circulating around the factory, told freely since Brandel hadn’t been to work in weeks. Customized memes were passed around, but for the participants waiting to collect their thousands—or tens of thousands—they weren’t funny anymore. People had taken days off trying to chase him down, only to get hit with a generic voicemail greeting, or one of those last-second excuses. The mental spending spree had faded into growing fears that the money might already be gone. Patience had been exhausted; it was time for confrontation. They were at Brandel’s place to settle up.

As soon as he spotted the car full of familiar faces, Brandel swung his truck down a side street, getting a head start on a Hail Mary run out of town. The tight confines of the area prevented the ordeal from evolving into a true high-speed pursuit. There was no race between pickup trucks barreling down the sloppy North Tonawanda streets. He was gone. Not just absent-from-work-for-three-weeks gone. He disappeared.

No one saw or heard from him the next day. In the information void, rumors were rampant. That he owned another property and was hiding out there. That he smashed his phone and couldn’t be tracked. That he blew the money. A coworker heard that one of Brandel’s family members had reported him missing.

He wouldn’t be seen again until 48 hours after the failed collection, when he cracked the window in his pickup and started howling for help in a supermarket parking lot.

* * *

During his time on the force, Moscato developed the kind of duality that allows him to take in the story while also chipping away at its foundation. Before passing Brandel on to an investigator at the police station, he had a feeling that the lone culprit was already sitting in the back of his squad car.

Moscato was careful not to confront Brandel—if his story was true, he had experienced a traumatic event. But there was no sign that anyone else had been in the truck—no accumulation of receipts or food wrappers that would suggest more than one person—despite the kidnappers’ having allegedly driven it around for nearly three days. Also, Brandel’s pants were dry. Kidnappers who would bag a coworker for $16,000, steal his truck and spend two days swerving through the snowy Buffalo tundra probably aren’t making time for their victim’s bathroom breaks. Moscato also noticed that Brandel’s goatee looked like it had been shaved recently. Another officer took a picture of the gas tank that was three-quarters full.

But this was the detail that made the officer struggle to remain in the confines of his courteous, Buffalonian timbre: In the pocket of Brandel’s black sweatshirt, also bundled in duct tape, were the keys to his truck. Unless some very courteous kidnappers did him the favor of cracking the window for him, Brandel, at some point, would have had to have had the keys in the ignition. How would they have ended up back in his pocket, encased in duct tape?

Back at the station, things soon grew clearer. Investigator John Spero is a Buffalo Bills and Notre Dame devotee who keeps a “Play Like a Champion Today” flag behind his desk. If he walked into the interview room as Knute Rockne, Brandel was the hapless, hopeless coach of a middling Midwest directional school.

Spero has spent his career interviewing devious people; it once took him 34 interviews with a suspect before the man admitted a crime (Spero said the man began to trust him during interview 27). Comparatively, cracking Brandel took all the mental finesse of a takeout order.

Spero allowed Brandel to hang himself during a back-and-forth that took place after he was Mirandized. Looking back on it, he said it was like watching a man trying to convince himself of the details of his own kidnapping. What color was the gun? Oh, it was uh, silver. How did you manage to sleep in that stash house? Um, they fed me NyQuil. He checked off nearly all the indicating body language of someone who wasn’t telling the truth—slumping, looking down at the floor, cradling himself in what officers call a “guarded position” and avoiding direct eye contact. Spero remembers Brandel sweating profusely on a Buffalo winter afternoon. Here was a man unraveling, clinging to the remaining shreds of a story he created to save his backside.

At one point, Spero asked Brandel about the location of his phone, which may contain some GPS data that could back up the story and start officers on the trail to find the kidnappers. Brandel said he remembered it being tossed by his captors on Route 18, the highway that runs parallel to the south shore of Lake Ontario. Spero suggested they could drive up and get it but joked that in order to find the phone in this weather, the kidnappers may have needed to put an ice scraper into the ground to mark the location underneath the fresh snowfall.

That was a plot point in another kidnapping scheme gone spectacularly wrong, when a bloodied Steve Buscemi ambled out of his car on the side of a deserted, snowy highway to bury a briefcase full of ransom money under a drift of ice and snow in the 1996 film Fargo.

“He didn’t get that,” Spero says. “But it was more for me.”

* * *

Who says the longest day of your life can’t last just an hour or two?

It took only barely 15 minutes in the interview room for Brandel to crack and admit that he’d arrived at the Tops alone. He tied himself to the headrest and duct-taped his own arms and legs. The entire interview session with Spero lasted about 35 minutes, which is almost the same amount of time he spent with police on the scene at the grocery store with Moscato.

He told Spero that some of the names in the pool were fake; everyone from the bar was Brandel. The owner of the bar Brandel referenced to colleagues denied a pool ever being run out of the place at all (after finding no evidence to the contrary, Sports Illustrated is honoring the bar owner’s request that, for fear of a negative effect on the business, the establishment not be named). Best that anyone can tell, there is no “Tim.”

Through tears, Brandel asked: “Am I getting arrested?”

“Unfortunately,” Spero said, “you are.”

In the end, Brandel was formally charged with scheming to defraud and filing a false police report. (He pled guilty to falsely reporting an incident, a misdemeanor offense.) His punishment included a restitution component; last summer he refunded most of the pool participants their entry fees, repaying some winners fully and cutting smaller take-it-or-leave-it settlements with others. Brandel made the drop-offs personally and collected signatures on handwritten notebook paper contracts that he returned to his parole officer as proof of payment. It was as awkward as you might imagine, near-wordless exchanges of cash, paper, pens and signatures.

His lawyer, Paul Buerger, scoffed at the idea of the district attorney’s office serving as a collection agency for an office pool, but figured that arrangement, plus a $1,000 fine and 100 hours of community service were worth it to avoid jail time. Then a judge sentenced Brandel to 15 days.

* * *

Brandel ultimately served seven days last August. He was let go at Unifrax. One year later, the question remains: Why, exactly, did he do it? For the money, of course, but what was his scheme? Despite sporadically responding to text messages, Brandel did not provide SI with any details regarding the pool or his fake kidnapping.

SI asked two participants in the pool to count the number of names they recognized out of the 100 squares. Their answers were 37 and 40, suggesting that more than half the squares may have been faked, giving Brandel overwhelmingly good odds of hitting something (and overwhelmingly bad luck on that Super Bowl Sunday). Perhaps, with a little planning and a little luck, a setup like this—trust from his fellow employees, an imaginary but believable set of additional participants, with no way for one side to reach the other—could have turned into easy money. Something of a grifter’s 401(k).

It’s unclear without confirmation from Brandel, but his payouts for the squares “touching” a winning square might have tipped the odds slightly more in his favor (a winning square on the edge would have only three “touching” winners, a box in one of the four corners would only have two); would the house keep the leftover thousands? The fact that it’s customary to tip the operator of a large cash pool also helped mitigate potential losses.

But it doesn’t appear Brandel was a spreadsheet jockey with a cutting-edge system. He wasn’t taking a fee off the top for running the pool, which would have been the easiest way to guarantee cash. Even now, multiple participants are satisfied that he wasn’t fixing the pool in the most obvious way: by assigning specific numbers to specific boxes rather than drawing them randomly. One coworker claims to have tracked down another colleague who had witnessed the random drawing, and the person maintained the drawing was legitimate. Plus, if the drawing was fixed, the 3–3 combination would surely have been assigned to a Brandel-owned box.

As far as anyone can tell, he simply bought out the majority of the squares, an unwise play considering the pot odds. Whether he never had the money to back the purchase of those squares and simply assumed he’d ultimately profit (or, at least, not go too deep into the red), or he squandered the entry fees over the course of the year, is unclear.

Some pool participants believe Brandel has been filling out the squares pool with fake names for years. A few think he’s a conman, or at the very least, reckless—did he care that getting busted might put everyone else at the factory in the crosshairs of management looking to squash out leisure gambling in the workplace? Could he understand the emotional drain on someone who had been told they had won a five-figure cash prize, only to string them along for weeks before revealing the money isn’t there?

In retrospect, everything about him became suspicious. When he was buying candy bars and picking up bar tabs, was he using their money to do it? Was he really a black belt? Did he really have that bad knee he talked about, or were rumors that he was once spotted carrying a 30-pack out of a neighborhood drugstore, then scaling the chest-high fence behind the store as a shortcut home, actually true? Who was the man they’d handed 500 bucks to?

Anyone found to have tied themselves up in their own car might be labeled strange; or at least the owner of a wild imagination. Depending on a person's experiences, mounting pressure causes synapses to fire in different ways. Who is to say, when the walls close in, we wouldn't have reasoned that the only way out is through a million-to-one bet to save it all? Strange is only what we haven't encountered until the parameters have dictated a new set of internal ethics. Strange could also be provincial. Do you follow Florida Man on Twitter? Would this crack the news in Niagara Falls?

* * *

Looking back, Moscato and Spero said that they felt bad for Brandel more than anything. They spent their careers arresting bad people, and they felt Brandel didn’t fit the category. Spero said he checked out Brandel’s background and found minimal criminal history, and nothing in the past two decades. All of the basic facts painted the mural of a normal person who went to exceptional lengths to cover up an embarrassing mistake.

That day last February, as he interviewed a flustered Brandel, Spero couldn’t help but wonder how it came to this. It was a story so outrageous that his relatives would later call and ask him about after hearing about it on the news in Oklahoma. It became fodder for Saturday Night Live’s Weekend Update (with a punch line that the perpetrator was Empire actor Jussie Smollett, whose unraveling after fabricated assault accusations was happening around the same time).

Why wouldn’t Brandel just take out a loan and use the money to pay people back? Why stage your own kidnapping, especially without a single rehearsal or dry run? How can a man go down a path of layering one embarrassing misdeed atop another?

Spero thinks back to the day he met Brandel, and how, as Brandel waited to get picked up from the police station, the investigator couldn’t help but ask one more time: Why?

“Once I was in, I was in,” Brandel told him, “there was no turning back.”

This story appears in the February 2020 issue of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

0 comments:

Post a Comment