Okung says NFLPA executive director DeMaurice Smith and his staff have used illegal methods to obstruct debate on the proposed CBA.

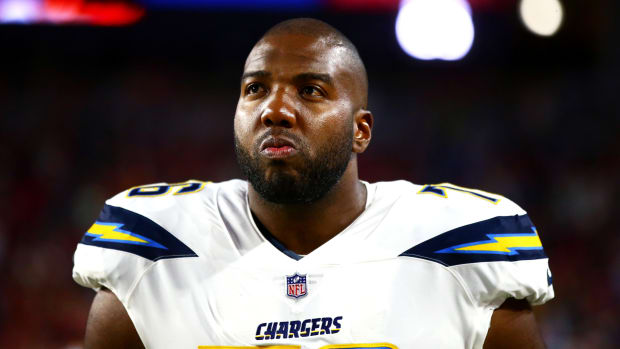

Russell Okung is an offensive tackle and not a quarterback. Yet the Los Angeles Chargers veteran hopes to call an audible on the NFLPA’s efforts to finalize a 10-year collective bargaining agreement with the NFL.

On Monday,

Okung filed an unfair labor practices charge against the NFLPA with the National Labor Relations Board. Okung, 31, insists that NFLPA executive director DeMaurice Smith and his staff have used illegal methods to obstruct debate on the proposed CBA. The players are currently scheduled to vote on the proposal by Mar. 14.Okung is one of nine vice presidents on the NFLPA’s executive committee. In late February, the committee’s 11 members voted, initially 6–5 and then 7–4, against recommending the proposed CBA. Okung is vying to replace committee president Eric Winston, an offensive tackle who will soon step down due to his retirement.

Unpacking Okung’s NLRB charge

The National Labor Relations Act is the governing law for Okung’s charge. Under the NLRA, Okung had six months from the date of an alleged wrongful act to file a charge.

Okung cites two types of violations. The first arises under Section 8(b)(1)(a) of the NLRA. Section 8(b)(1)(a) makes it illegal for a union or its representatives to restrain or coerce employees in ways that violate their rights. Those rights are detailed in Section 7 of the NLRA. For instance, unions can’t punish or threaten members who organize campaigns that union leaders oppose. As a result, members who collectively criticize leadership’s strategies in CBA negotiations have a protected right to express their views. Section 7 also guarantees members the right to talk about the union itself, including in fault-finding ways. Likewise, Section 7 bars unions from spying on members’ activities or creating the impression that spying is taking place. It also forbids unions from adopting formal and informal policies that are designed to inhibit dissension.

In his charge, Okung claims that NFLPA leadership threatened to retaliate against him and other NFL players “if they did not join or support the union.” If this claim proves true and verifiable, the NFLPA would have violated Section 8(b)(1)(a). A union can’t threaten to retaliate against members for not supporting the union itself.

Okung maintains that Smith, Smith’s staff and outside counsel all violated the NFLPA’s constitution, a document that governs the relationship between the NFLPA and its members. They did so, Okung insists, by trying to interfere with his protected rights.

To advance his argument, Okung highlights Section 6 of the NFLPA constitution. Section 6 mentions the union’s negotiating committee, which is tasked with representing the interests of members in CBA discussions. Pursuant to Section 6, the negotiating committee “shall consist of executive committee, including the executive director (Smith) serving ex officio.”

Okung maintains that Smith froze out the executive committee, in contravention of Section 6, and then wrongly submitted a CBA offer after the committee had opposed it. Further, Okung insists that Smith tried to “bypass” the NFLPA’s board of representatives—a group that includes a player representative from each of the 32 teams along with alternate reps. Okung contends that Smith forwarded a CBA offer to all NFLPA members without gaining the approval of the board.

Okung identifies two persons associated with the NFLPA as making “threats.” The first is David Greenspan, a prominent attorney who provides outside counsel to the NFLPA and to various players, including Tom Brady during the Deflategate litigation. Okung claims that Greenspan made a threat on Oct. 31, 2019. The charge doesn’t detail the nature of the threat or how it was transmitted. Smith is the second person Okung identifies as making threats. Okung claims that Smith’s alleged threats are occurring on an “ongoing basis” and continue to this day.

Okung maintains that these threats have been pervasive and chilling of members’ rights. He asserts that Smith and others have tried to suppress his right to speak up. They have also, Okung asserts, taken similar measures to block other dissenting players. Okung goes so far as to claim that in retaliation for him warning members that NFLPA leaders have (in Okung’s opinion) violated the union’s constitution, he has been subjected to an abusive NFLPA investigation. Okung further alleges that he has “been threatened with criminal prosecution and union sanction.”

Okung’s charge also invokes Section 8(b)(3) of the NLRA. Section 8(b)(3) makes it illegal for the NFLPA to refuse to bargain in good faith in regard to wages, hours and other working conditions. In order to satisfy Section 8(b)(3), the NFLPA must bargain with an open mind and fairly on behalf of all of its members. The NFLPA is also prohibited from going through the motions in negotiations. Likewise, the NFLPA can’t advocate for provisions that are discriminatory or illegal.

NFLPA’s likely defenses

There’s a lot to unpack in Okung’s charge. It levels serious and damning accusations against the NFLPA’s leaders, especially Smith. Okung paints the NFLPA as a union that not only doesn’t represent the majority’s will but that also conspires to unethically quash opposing voices.

That said, we have only heard one side of the debate. A charge can be rebutted by the charged party, in this instance the NFLPA, which will have an opportunity to try to debunk Okung’s assertions.

As a starting point, the NFLPA will likely insist that Okung’s charge contains factual inaccuracies, distortions and exaggerations. It remains to be seen if Okung possesses corroborating evidence of the alleged threats. The NLRB form for filing a charge disallows a charging party (Okung) from supplying a detailed account of the claims. Likewise, the form bars the naming of potential witnesses. Okung will need to provide those details to NLRB agents who are assigned to investigate his charge.

Even if there is evidence of “threats,” not all threats are equal or, for that matter, illegal. It’s possible that Smith and others vocally disagreed with Okung. Perhaps they strongly or even forcefully encouraged him to adopt their viewpoints. Heated disagreements, particularly in the context of a contentious negotiation, happen within unions. Those disagreements can also lead to hurt feelings and perceptions of unfairness. Those sorts of outcomes, however, might not rise to the kind of procedural unfairness that establishes an NLRA violation.

The NFLPA is also poised to raise criticisms of Okung and his conduct within the union. Okung can expect that NFLPA staff and attorneys will carefully scrutinize him, and his recent activities, in order to uncover any evidence of questionable conduct on his part. It’s safe to assume the NFLPA will portray him as combative and uncooperative.

Further, the NFLPA is positioned to assert that Okung’s interpretation of the league constitution is incorrect. The NFLPA will maintain that it has adhered to all procedural requirements. The stronger the factual record for the NFLPA, the more convincing a defense it can offer.

The NFLPA is also poised to mention that while Okung might genuinely feel Smith could have negotiated a more advantageous CBA for players, that line of critique can almost always be brought against an executive director of a players’ association. The NFLPA will stress that whether the proposed CBA is “good enough” for players is ultimately up to the players.

Next steps in Okung’s NLRB charge

Okung’s charge will take time to play out. A decision on the merits normally takes two to four months. This means a decision might not happen until the summer.

In the coming weeks, the NLRB will assign agents to gather evidence pertaining to Okung’s charge. This gathering process will certainly include the collection of pertinent emails, texts and memoranda. It might also entail the taking of affidavits of Okung, Smith and other relevant witnesses—including fellow members of the executive committee and Okung’s teammates. Keep in mind, an affidavit is a sworn, written statement. A person who knowingly lies in an affidavit can be criminally charged with perjury.

After evidence is collected, a regional director of the NLRB will review the case. If the regional director finds that Okung has showed probable merit of a violation, the director will issue a complaint detailing the findings. The director can also petition a U.S. federal district court judge for a temporary injunction that would order Smith and others to stop illegal practices.

Whether or not that petition happens, the issuance of complaint by the regional director would lead to a new phase of the legal process: a hearing before a NLRB administrative law judge. This hearing would resemble a trial and would adhere to the federal rules of evidence and procedure. The administrative law judge would issue a ruling that could be appealed by the losing side to the NLRB in Washington D.C. Ultimately the NLRB could issue a cease and desist order to stop an unfair labor practice.

If this process sounds complicated that’s because it is. It could take many months, and possibly years, to play out.

Alternatively, if Okung fails to persuade the regional director of the probable merit of a violation, the charge will be dismissed (a dismissal, however, could then be appealed to the NLRB’s general counsel).

Okung faces challenging odds. Last year, there were 18,552 unfair labor practices charges. Of those, only 916 led to the issuance of complaints (6,061 were instead resolved through settlements). To that point, the NLRB strongly encourages settlement discussions. This means the NLRB will advise both Okung and the NFLPA to work out their differences amicably.

Impact of Okung’s NLRB charge on CBA negotiations and NFLPA vote

NFL players will vote on the proposed CBA by Saturday, Mar. 14, at 11:59 pm. The proposal will pass if a majority of members vote “yea.”

As detailed elsewhere on The MMQB, there are a host of divisive issues in the proposal. They include an increase of the regular season from 16 games to 17 games and an expanded playoff to one that involves 14 teams, meaning 44% of the league’s 32 teams would make the playoffs. The proposal also calls for a 20% increase in the minimum player salary from $510,000 to $610,000. A number of attorneys who represent NFL players have been highly critical of the proposal, particularly with respect to potential adverse impact on players’ health. Brad Sohn and Ben Meiselas are among those attorneys.

A “no” vote wouldn’t trigger an immediate labor crisis. The current CBA runs through Mar. 3, 2021. The league and NFLPA would use the current CBA for this upcoming season. It’s possible that both sides could negotiate another CBA proposal in the weeks and months ahead. If no deal is eventually reached, the possibility of NFL owners locking out the players on Mar. 4, 2021 would become a legitimate concern.

Okung’s charge will not stop a vote from happening. As detailed above, the process by which a charge is reviewed for classification as a complaint normally takes in the ballpark of two to four months. Further, even if Okung succeeds in securing a complaint, the complaint wouldn’t necessarily trigger immediate action or injunctive relief. A regional director and federal district judge would likely be hesitant in unwinding a CBA that a majority of members support (assuming the majority vote on Saturday is “yea”). A complaint would bring about a hearing before an administrative law judge and possibly a subsequent appeal that occurs over a period of months if not longer. The legal process moves at its own pace.

Still, Okung’s charge might dissuade some players from voting in favor of the proposed CBA. If the players are inclined to believe Okung, they would also believe that he and likeminded players have been effectively railroaded by NFLPA leadership who were told by a majority of the executive committee to negotiate a better CBA. However, if players believe Okung is merely using the NLRB process as a last resort to stop a satisfactory CBA, they probably would be less inclined to find his charge as a meaningful reason to vote nay.

We’ll soon see how it all plays out.

Michael McCann is SI’s Legal Analyst. He is also an attorney and the Director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute at the University of New Hampshire Franklin Pierce School of Law.

0 comments:

Post a Comment